Last year, the Best Actor category was one of the most exciting for the Oscars. You had a legitimate three-way race between Colin Farrell, Austin Butler, and eventual winner Brendan Fraser. You also got a bit of a reprieve from the coronation ceremony for Everything Everywhere All at Once – assuming you wanted one – as this was the only “major” category (it won Original Screenplay so it obviously wasn’t up for Adapted) where the eventual Best Picture winner wasn’t nominated, preventing it from being the first “Big 5” sweep since The Silence of the Lambs.

This year, unfortunately, the intrigue is dialed way down. To be clear, four of the five nominees this time out gave spectacular performances (guess which one didn’t), but the result is very much NOT in question. This is Cillian Murphy’s to lose, and has been since Oppenheimer‘s release back in July. Paul Giamatti won the comedy side of this category at the Golden Globes, but the relevance for that particular prize is almost nil at this point. We’ll know for certain in a couple of weeks, once the BAFTAs and SAG have their say, but this feels like a done deal.

As I’ve mentioned, I’m not the biggest fan of foregone conclusions, especially in the big contests, but the tea leaves are what they are. So the question remains, does Murphy deserve his impending victory? There’s only one way to find out.

This year’s nominees for Best Actor are…

Bradley Cooper – Maestro

I’ve been a fan of Bradley Cooper for a long time, pretty much since The Hangover. That film and its sequels haven’t exactly aged well, but Cooper showed off remarkable range even in that raunchy comedy, and he’s mostly only gotten better with time. That said, I hated this performance.

The entirety of Maestro feels like an exercise in self-indulgence, a demand from Cooper himself that everyone see him as a genius. And honestly, if people didn’t see him that way before, they sure as hell won’t now. His turn as Leonard Bernstein is the height of ego, meticulously engineered to campaign for awards, and it’s painfully shameless.

But even if you set that aside, there’s really not much to the actual, well, ACTING, in this piece. Like Nicole Kidman in The Hours before him, half the “performance” is the prosthetic nose (Kidman got her Oscar for that, so let’s hope history doesn’t repeat itself). There’s been some mild controversy over whether the usage constitutes “Jew-face,” but I think that’s kind of absurd. The makeup team simply made him look as close to Bernstein as possible. The problem is in how it affects his mannerisms on camera, as his vocal imitation of Bernstein sounds like it came as a result of having too much gauze and plaster shoved right up his schnoz. I said in my review of the film that he sounds like George Takei with a head cold more than he sounds like the actual composer. When someone’s voice is that distinct, you either have to nail it or not bother.

The other half is the manic energy behind Bernstein’s various vices. Playing like an E! True Hollywood Story dramatization of Academy box checks, Cooper spends most of the film drinking, drugging, and fucking random dudes. If that’s what you’re into, fine, but you know what we didn’t see at all in this? Bernstein’s creative process, his writing style, basically anything that makes him a compelling person outside of the clichés. We get the tiniest bit of insight when the coke binge passion spills over into a conducting performance, but that’s about it. Part of that problem is the directing, part of it is the writing, and part of it is the acting. And since Cooper was responsible – at least in part – for all three, the whole thing translates as a failure on his part.

Colman Domingo – Rustin

Domingo’s role is quite similar to Cooper’s, but there are miles between the two in terms of the quality of the performances. For one thing, Domingo’s affectation of Bayard Rustin’s voice doesn’t sound nearly as terrible. For another, his sexual identity is a crucial part of the characterization, rather than basically the entirety.

But most importantly, for Domingo, his performance carries the story and propels the narrative forward. I confess that I had never heard of Bayard Rustin before seeing this film, and I’m guessing a lot of other people are in the same camp. As such, the film focuses on showing just how significant his role in the Civil Rights Movement was, and Domingo picks the appropriate moments to stand his ground or step back and work as part of the larger group that was attempting something so historic.

He’s a role-player, a crucial role-player, and sometimes that means NOT making it all about yourself. The plot of Rustin keeps this balanced, and Domingo plays the scenes appropriately, while still being a commanding enough presence to draw your attention in the moments where other influences are having their say, his quiet reactions carrying as much thematic weight as his spotlight monologues. This is a Best Actor showcase in the truest sense, but Domingo does enough to distinguish himself because he plays a side character taking center stage, and handles both demands with dignity and power. That’s extremely difficult to pull off.

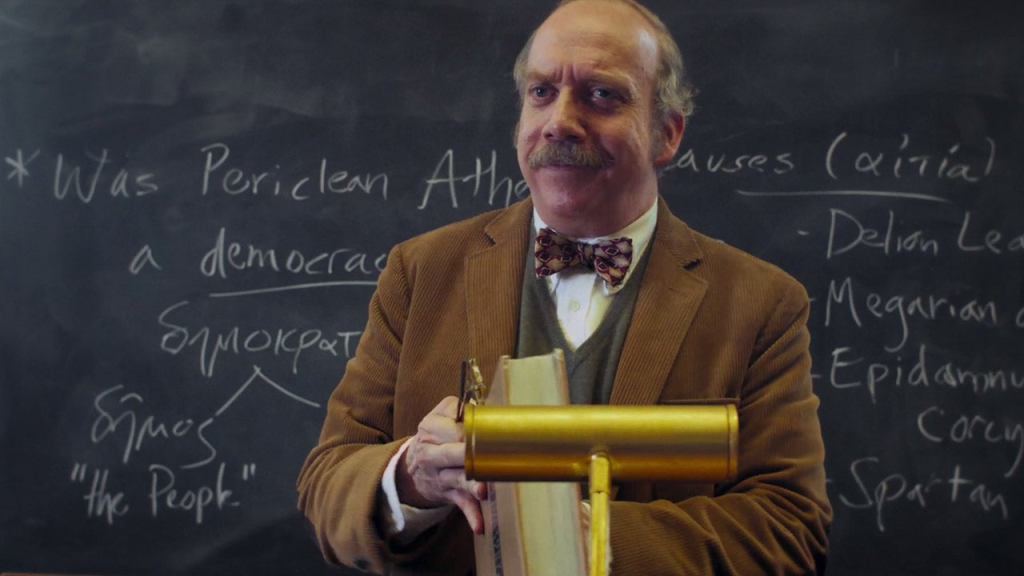

Paul Giamatti – The Holdovers

If there’s anyone in this field who can legitimately make the case that they’re “due” for a win, it’s Giamatti. The man has had a solid career for over three decades, with tons of accolades, though somehow he didn’t get nominated for Sideways (just goes to show how much the Academy used to hate comedy). He’s not just a great character actor, he’s a great actor full stop, and The Holdovers gives him his best chance to shine in years.

We all have a soft spot in our hearts for the loving curmudgeon, and Giamatti’s turn as Paul Hunham fits it to a tee. He gets most of the best lines, delivers them with excellent emotion and comic timing in equal measure depending on the needs of the scene, and moves in a delightfully animated fashion, even in the quieter moments.

But the real highlight of his performance here comes in the thematic seriousness of his character, especially as it relates to his two companions in the film, Mary and Angus. In the young Tully, he sees a version of himself. The boy is smart, cunning, and quite resourceful. But given his record at previous schools and his penchant for rule-breaking, Paul sees that Tully is in danger of making the same mistakes he did, and becoming as miserable as he is. As such, like a reformed Scrooge, he looks at Tully as a means of atonement, a chance to change his own ways and lead by benevolent example, so that he can set things right for a promising lad who has a shot at a better future. He’s his own cautionary tale, worn down by bitterness and the stark unfairness of a world that refuses to play by its own rules. Tully is on the precipice of falling into the same traps he did, and despite constantly coming to loggerheads, Hunham commits himself to doing right by the kid.

When it comes to Mary, Paul sees not an outlet for redemption, but one of continued education. Paul may work as a teacher, but he is eternally a student of life. There is never a moment where something cannot be learned, and it’s through his interactions with Mary that he gets that continuous reminder. Having to repeatedly step outside of his narrow worldview, he gets an objective perspective from one of the only other staff members left at the school during the holiday break, forming a crucial rapport and gaining an understanding about how his peers perceive him. While their professional positions put them at different social and economic stations, Mary wastes no time pretending they aren’t equals, and never fails to call him on the carpet for his bullshit. That Giamatti is able to take those moments and adjust his performance as he goes shows not only the progression of the character but the strength of his acting ability.

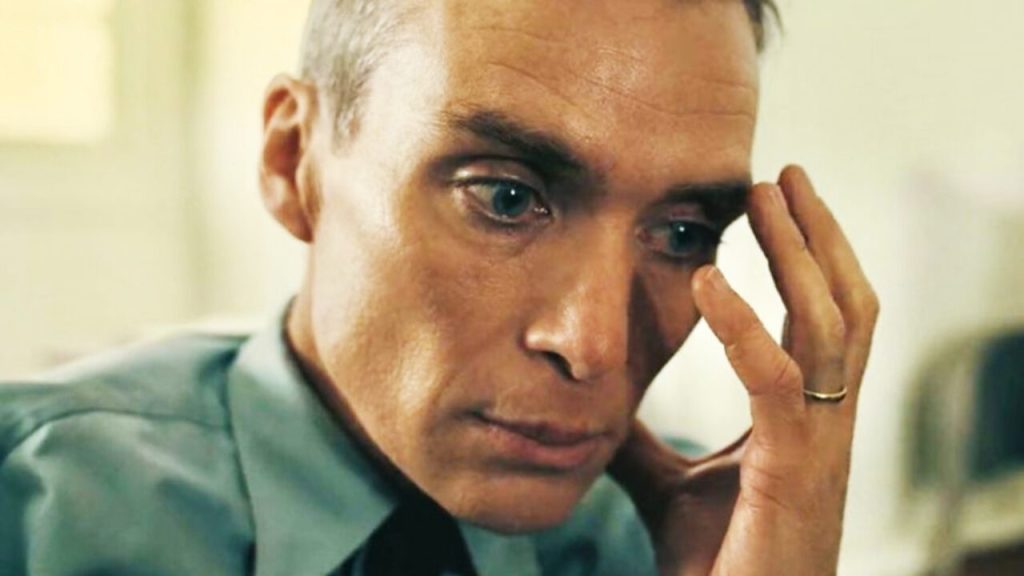

Cillian Murphy – Oppenheimer

I’m a fan of Doug Walker, aka the “Nostalgia Critic,” and when he reviewed Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy a while back, he made an interesting point when it came to Cillian Murphy, who played the Scarecrow through all three films (though he’s only a principal antagonist in Batman Begins). He noted that at the time (2005-2012), Murphy had the acting chops to pull off the role, but just looked too young to be convincing. If he were 10 years older, it would have worked so much better.

That stuck with me a lot watching Oppenheimer, because it is now more than a decade later, and you can tell that Murphy has truly aged into this title role. Don’t get me wrong, he’s always been a great actor, but for this film, more than any other in his career, you feel the weight of time. The character ages and matures over the course of the movie, but there’s a constant discipline to Murphy’s performance where you see the accumulation of his years of experience.

As to the character of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Murphy has to demonstrate incredible range over the film’s two timelines. As a youth he’s smart but impetuous. When he begins rising up the academic ladder he’s brash and egotistical, with quite a high opinion of himself. He conducts himself with class and humor in pretty much any prolonged discussion. As we get closer to the Trinity Test, he becomes more stoic and reserved, calculating the possible outcomes of every situation. By the time he’s basically put on trial, he’s resigned to his fate, and even a little inarticulate, but he’s still sure of the facts and truths that he has in his mind. Each of these iterations show that Oppenheimer is a brilliant but deeply flawed person. And through it all, Murphy captivates the audience with this ability to almost see beyond the fourth wall, developing a thousand-yard stare that’d put the entire cast of Full Metal Jacket to shame.

All of this follows the progression of the story and its two divergent paths. When Oppenheimer is studying and eventually working on the bomb, he moves with a fast, deliberate pace through his scenes and dialogue, a testament to the potential of scientific exploration that he embodies. Once the nukes are dropped, however, there is only the cold data and the fallout, leaving him slower to act and speak, because now that the “experiment” has been carried out, there is only what is and what isn’t, and he must constantly steel himself to that reality. It’s a fantastic performance from beginning to end.

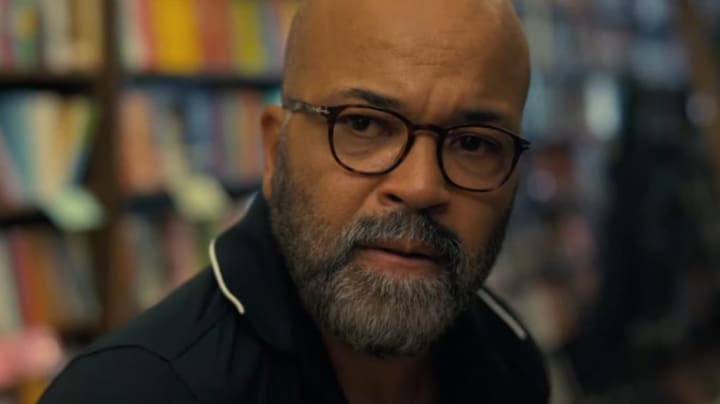

Jeffrey Wright – American Fiction

I feel kind of bad for Jeffrey Wright. As great as Paul Giamatti’s performance was, I look at Wright the way I looked at Hugh Jackman in Les Misérables over a decade ago. I remember thinking then that Jackman would be a lock to win Best Actor for his performance as Jean Valjean in any year where Daniel Day-Lewis wasn’t playing Abraham Lincoln, and that sentiment applies to Wright here. If he made American Fiction in a year where Cillian Murphy didn’t play J. Robert Oppenheimer to near perfection, this would be his Oscar almost without question, at least in my mind.

Maybe I’m a bit too biased, but part of the reason I loved Wright’s turn as Thelonious “Monk” Ellison is because he expertly and consistently pulled off what I call “REALLY?!” Face. It’s this incredulous look you get when forced to react to something monumentally stupid, especially when it’s said and done with no hint of irony. I make that face ALL. THE. TIME! It’s honestly gotten me into trouble on a few occasions. I like to think that I have a decent poker face in most situations, but when confronted with something truly idiotic, sometimes I can’t help myself, and Wright puts on that face with effortless panache.

It’s hard to extricate yourself from your own personality and see yourself as others see you, which is a conundrum that Wright demonstrates quite admirably. Like Giamatti’s character, he believes in a meritocracy based on facts and reality, and that skill should win out over privilege, pandering, or gamesmanship. It’s somewhat more significant coming from Ellison, who was raised in a privileged household, part of why he refuses to be pigeonholed into black victimization paradigms. He sees a rival in Issa Rae’s Sintara Golden, not because she wrote about life in the ghetto, but because she did so despite being highly educated, and unapologetically did so to play to an audience, and Monk just can’t tolerate that. Part of the fun of the film is that both sides are given validity, but a lot of the fun of Wright’s specific performance is that he personally won’t be so generous.

There’s a lot that I relate to when it comes to Monk. Professional frustration? Check. Family drama? Check. Shouldering the burden of watching your mother deteriorate? Double check. Bad luck in romance? Oh yeah. Substantively, the biggest difference between he and I are our vocations and our races, and he’d be the first to say that the latter element shouldn’t even enter into the equation, not because he wants to deny identity politics, but because it’s not relevant within context. He makes very fine distinctions, what some might call nitpicking, and Lord knows I’m guilty of that as well. So yeah, Cillian as Oppenheimer might be the best performance, but Wright as Ellison is the character I most cling to.

***

So, does Murphy indeed deserve to win? In my opinion, yes. It’s a once-in-a-career type role, and he embodies it about as well as anyone could have hoped for, showing the most versatility of any of this year’s nominees. That said, my heart is somewhat with Wright as well, and I’d be thrilled if he pulled the upset.

My Rankings:

1) Cillian Murphy

2) Jeffrey Wright

3) Paul Giamatti

4) Colman Domingo

5) Bradley Cooper

Who do you think should win? Vote now in the poll below!

Up next, I didn’t accomplish my goal this year to see the entire shortlist, but that doesn’t mean we can’t rank 14 non-fiction films for shits and giggles. It’s Documentary Feature!

Join the conversation in the comments below! What do you look for in a great performance? Would you swap out any of the nominees for another actor? Do you prefer dramatic or comedic leads? Let me know! And remember, you can follow me on Twitter (fuck “X”) and YouTube for even more content!

One thought on “Oscar Blitz 2024 – Best Actor”