If you’re a regular reader, you might have noticed a bit of an unintentional trend in recent years. As time has gone on, one of the odder changes in how I view films is that I find myself much more aware of runtime. A big part of this is just the fact that I’m a diabetic, and one of the ways it affects my life is that I tend to go the bathroom more often than others, and/or when I go, the session lasts longer. I remember a few years ago, purely as a goof, I had my then-girlfriend time me on a pee break. I went for a solid 2:07. My kidneys are world class!

As such, I’ve had to adapt and fine tune my habits when going to the movies. I typically have a wee before I leave for the theatre, one more after I arrive, and a final one after the trailers are done but before the movie starts. That last part only applies at AMC, because the trailers alone take up 20-25 minutes, and afterwards there are always two or three more ads about AMC itself, including the Nicole Kidman bullshit. I typically have two and a half minutes from the end of the last preview until the first logos for the flick go up on screen. I’ve got this shit down to a science to make sure I’m completely empty so that I don’t miss anything of consequence.

Setting that aside, the last few years I’ve just become more attentive to how and when movies pad themselves out. I’m not talking about long takes or artistic cinematography that lingers on a scene for dramatic or thematic effect. I’m talking about scenes where exposition we’ve already gotten is repeated for no one’s benefit, or when an action scene keeps going for far too long because a bunch of idiots are still shooting bullets at Godzilla knowing they don’t hurt him, or any number of gratuitous fart jokes.

For example, I just watched Captain America: Brave New World the other day. A full review is coming, but there was a scene that perfectly illustrated what I’m talking about. At the beginning of the third act, as the Marvel formula dictates, the new Cap, Sam Wilson, is feeling down. In a scene that’s meant to be solemn, there’s a knock on the door. Sam says that no one is supposed to enter, but in steps the Winter Soldier, Bucky Barnes, because part of this movie’s Disney+ homework was watching The Falcon and the Winter Solider to understand why Sam now carries the shield. They talk about nothing for about five minutes, Bucky gives a speech about power and responsibility like he’s badly misquoting a Spider-Man movie, Sam quips about Bucky having “his speechwriters” polish that monologue (apparently Bucky’s running for Congress, which has no bearing on anything plot-related), and then Bucky fucks off. A moment later, one of the new characters comes in the room, not even bothering to knock, and comments to the air about having just seen “James Buchanan Barnes.” WE FUCKING KNOW BUCKY’S FUCKING NAME! YOU HAVE CONTRIBUTED NOTHING! There’s letting a moment breathe, and there’s just plain old inefficiency.

I notice this more now because I’ve spent so much time covering short films, either at festivals or here on the Blitz when they get nominated. I see the various tricks and methods used to keep a story tight, with the filmmakers fully aware that they only have 40 minutes to get their point across. It’s become so ingrained into my viewing experience that I honestly lost count of how many times over the past few years that I’ve said something tant amount to “This could have been a short” in a review. Hell, just with this year’s Documentary Feature shortlist I remember thinking it for at least six of them. It’s especially crucial with docs because most people can only watch them on the various streaming services, so it’s even more incumbent on the creators to keep the audience’s attention and not let them waver to something else in their queue or go to a different screen entirely.

This is what I mean when I keep harping on the point to “take as much time as needed to tell the story properly.” Sometimes, yeah, that’s three hours or more, because there are deep dives that must be taken for the sake of character, context, subtext, and narrative logic. But on the flip side, sometimes that just means you need a bit more discipline in the editing booth. If you’re repeating stuff we already know – or even worse just repeating shots – then just be honest and admit you don’t have enough content for a feature, and adjust accordingly. This is especially true if you’re making a documentary, because in most cases you’re dealing with subject matter that is inherently not exciting, and you can’t risk the viewer getting bored.

This year’s nominees for Documentary Short are…

Death by Numbers – Kim A. Snyder and Janique L. Robillard

Just over 20 years ago, Michael Moore won the Academy Award for his feature-length documentary, Bowling for Columbine, a film that employed Moore’s gonzo style of filmmaking to explore and confront America’s obsession with guns. The goal was to shine a light on our unique national identity when it comes to firearms, particularly why so many people feel the need to stockpile personal arsenals of literal weapons of war which they are not properly trained to use, and why no matter how bad things get with mass shootings, especially when the victims are schoolchildren, the response seems to be platitudes about “thoughts and prayers” without any action to fix the problem. One of the most baffling things Donald Trump ever did (and that is saying something) was on his first day in office in 2017, where his first act was to repeal a law that made it harder for those judged to be mentally unstable to buy guns. For all the talk from him and his party about mass shootings being a mental health issue, his first priority as President was to make it easier for them to kill.

The way kids have had to adapt to this epidemic of violence since Columbine has been heartbreaking to say the least. Increased police presence in schools, including poorly-trained officers who use the post as an opportunity to bully students, a cottage industry in see-through and bulletproof backpacks, active shooter drills, and so much more have permanently altered how we have to educate our children. When I was in school, it was a monthly fire drill and twice a year we had a Cold War holdover in the form of a “civil defense” drill where we had to duck and cover in the event of a nuclear blast that we all knew was never coming. We were done with those forever by 8th grade. Kids today would be over the moon to only have to worry about that much.

Back in 2009, I tried my hand at writing a novel for the first time. It was going to be a horror book about a school shooting. I hadn’t really seen any literature on the subject (I later read Douglas Coupland’s Hey Nostradamus! on a recommendation as I was writing; it’s worth your time if you can stomach it), and I figured I could make it legitimately scary because the most terrifying things are the ones that can actually happen. Well, it did happen, and it kept happening. In 2012, as I was trying to finish the first draft, Sandy Hook went down about 50 miles from where I was living at the time. I couldn’t even look at my manuscript anymore. It was all too real. Even thinking about it made me nauseous. Another decade on, nothing has changed, and the reality has only gotten worse.

This is the backdrop for Death by Numbers, written by and starring Sam Fuentes, one of the survivors of the Parkland shooting in 2018, where 17 people were killed and 17 more injured (Sam was shot in the leg). I watched the screening on February 14, Valentine’s Day, literally seven years to the day since the massacre. Centered around the sentencing trial of the shooter (he pled guilty upon his capture, the trial was to determine if he’d get the death penalty), the film uses Sam’s ongoing process of overcoming her trauma, supplemented by journal entries that use the statistics of that day (she states ironically that she was never good at math, but these numbers are forever seared into her brain), to show not only the lasting damage for those who lived, but to highlight their strength, as the trial is a rare opportunity to confront the killer, as in many of these cases the shooter dies at the scene, either by their own hand or very belatedly by law enforcement, the so-called “good guys with guns.”

The film is superbly made, taking us through the confusion and doubt that Sam experiences as the time draws near to her testimony – which she was subpoenaed to give, she’d have rather avoided this altogether – and as she prepares to give an address directly to the assailant at sentencing, an allowance given by Florida courts to victims. We hear her muse about the girl she was before that day and the damaged woman she is now, picking up the pieces of her life in hopes that they can be put back together someday, but fully aware that she may never succeed. She’s also very thoughtful about what should or should not happen to the shooter, wondering if justice will actually be served if he’s put to death. He’ll either be executed or receive a life sentence without parole, so no matter what he’ll spend the rest of his days in prison and die there. The question is whether it’s right to use the state as a tool for revenge, and if killing one individual will help anyone heal. She knows she can’t answer that question for anyone but herself, and she realizes that she can’t even come to a decision just for her own peace of mind. It’s just too complex. She understands that her future will be messed up no matter what happens, all because some hateful prick thought he’d be a hero to even more hateful pricks by ending innocent lives.

This is a heartbreaking film to watch, but an essential one, because it shows what real strength is. The boy with the assault rifle thought that made him strong, but it didn’t. It made him a coward, because he wouldn’t have dared attempt his killing spree with his bare hands, or even a knife. He had to make sure that his victims couldn’t defend themselves. That is weakness. People like Sam are strong, because they use their unspeakable trauma to fight for change, working towards real solutions to end this crisis, or at least mitigate it. One of the best touches in the entire movie is that the killer’s face is only fully shown once, at the very end, when Sam’s had her say. Every other time the courtroom footage switches to him, a marker effect is used to scribble him out. He will not get anything resembling sympathy or positive attention, and he never will.

I Am Ready, Warden – Smriti Mundhra and Maya Gnyp

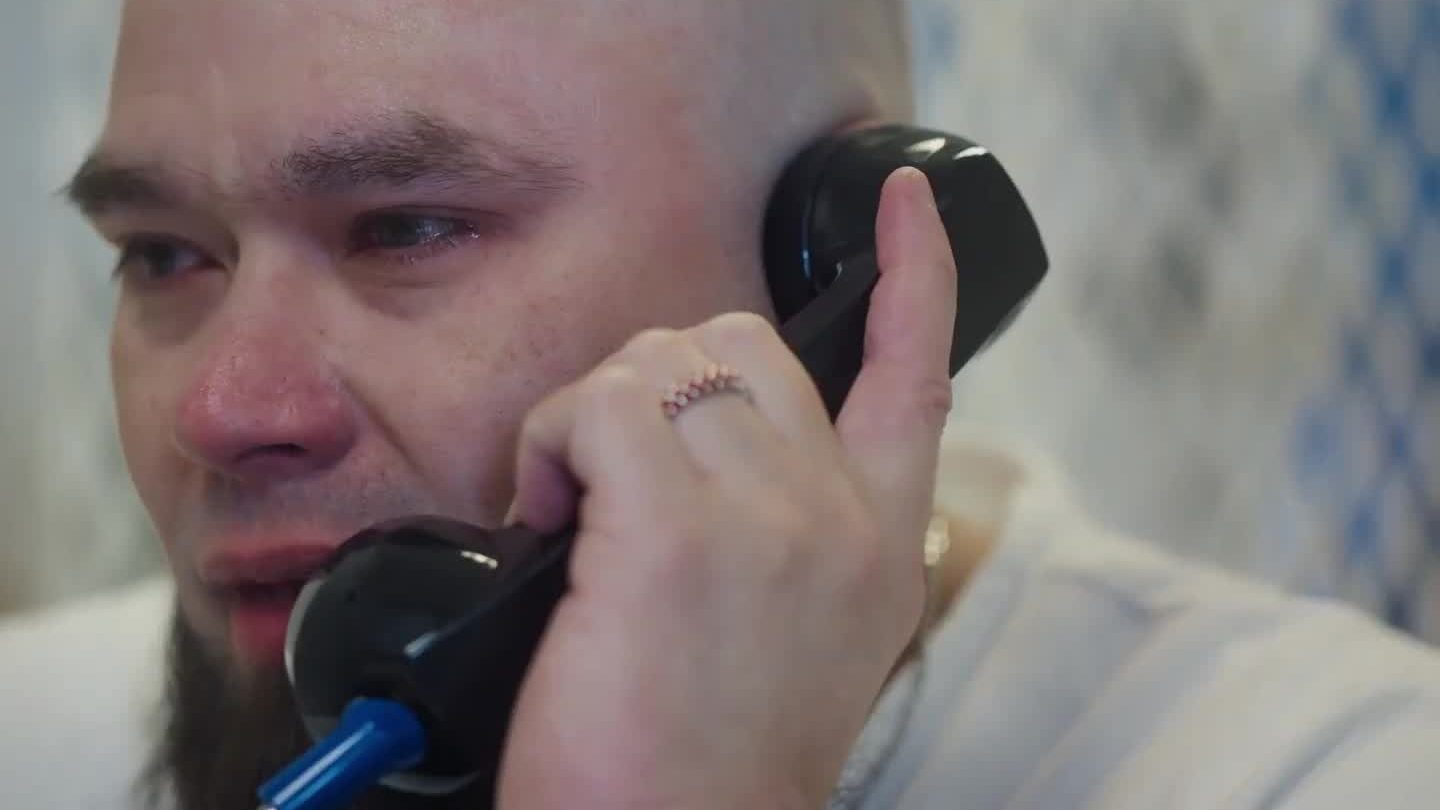

In 2004, John Henry Ramirez stabbed a man to death at a Texas convenience store. After four years on the run in Mexico, during which time he had a child, he was captured, convicted of murder, and sentenced to death. A former Marine with a very troubled past, Ramirez apparently reformed himself in prison, and appealed for a commutation, supported by local spiritual leaders who had gotten to know him. His request was denied, and he was executed by lethal injection in 2022.

The film, I Am Ready, Warden reflects Ramirez’s final words, and serves as an encapsulation of his emotional growth and acceptance of what he’s done. Like Death by Numbers, the documentary examines whether or not capital punishment is truly a form of justice, as the man killed by the state is demonstrably not the same person – behaviorally at least – who committed the crime, and openly questions whether this ultimate punishment actually brings closure to the victim’s survivors.

The story is told from multiple perspectives. The first, obviously, is Ramirez himself, who reflects on what he did, expresses remorse, and fights for his own survival as a means to at least do some good in the world to make up for his wrongs, even though he knows he’ll never be able to make amends for taking another man’s life. His time in prison led to a religious awakening (not featured in this film is the fact that he successfully sued all the way to the Supreme Court to allow his pastor to be physically present in the execution chamber and lay hands upon him as the sentence was carried out), and we hear from Pastor Dana Moore and chaplain Jan Trujillo, both of whom wrote to Governor Greg Abbott directly to plead for clemency. Trujillo especially asserts that she was always in favor of the death penalty until she met Ramirez, concluding that ending his life would be a sin, as it would be removing someone who had come to God from this world, rendering it impossible for him to preach gospel. We also hear from Ramirez’s son, Israel, who has to cope with the fact that his father is about to die for doing something awful, but it all happened before he was born. County DA Mark Gonzalez, who is vehemently opposed to capital punishment, actually tried to rescind the death warrant when he took office.

But the big juxtaposition comes in the form of Aaron Castro, the victim’s son, who was 14 when Ramirez killed his father. As he follows the case on various news outlets, he becomes increasingly disgusted about the possibility that Ramirez might be spared. The irony of losing his father to homicide while advocating for Israel to suffer the same fate doesn’t even enter into his mental calculus. He’s been fighting for half his life to see Ramirez dead, because he believes that will finally allow him to heal. How he reacts once the deed is done is some powerful stuff.

This is an insightful treatise on the issue, because there are no easy answers. For example, I hate the idea of the government having the power to kill a citizen, and there are very few scenarios where I feel it’s warranted. For me, the crime has to be super heinous to justify the action, and from a pure economic standpoint, if the only other option is life without parole, then it might save resources to just get it over with. However, it should definitely be seen as a last resort, not the first, and Texas’ particular boner for executions is disturbing in the extreme. Just given the two cases in these first two entries, had I been on the respective juries, I would have advocated for sparing Ramirez, but I could have condemned the Parkland shooter. But even then, I have to be absolutely certain that the guilty party is irredeemable, and that there’s no possible scenario where they might be innocent. The cavalier nature with which this nation has executed those who were either later exonerated or that had very reasonable doubts about their guilt is staggering, and the number of Death Row inmates who are eventually cleared before they’re strapped to the gurney should be more than enough evidence for a nationwide moratorium.

What makes this a great documentary is that we don’t waste any time pretending that Ramirez is innocent, or in attempting to build suspense that he might live. The opening of the film is a video recorded by Ramirez letting us know right off the bat that if we’re watching it, he is dead, “murdered by the state of Texas,” as he puts it. That frees us up as viewers to focus on the campaign for his life, as well as the consequences of it ending. If you want to make a case for social and political change, you can’t just say that something is right or wrong on moral grounds. You have to show us what something like this actually means, both for proponents and opponents, and the film accomplishes exactly that.

Incident – Bill Morrison and Jamie Kalven

Speaking of people being murdered by the state, police violence! It’s an all-too-common problem in society, especially when the deadly actions are disproportionately taken against minority citizens by white cops. The entire reason the Black Lives Matter movement exists is because there are far too many instances when law enforcement has defaulted to using deadly force against black people during encounters, whether or not they were armed or suspected of a crime, and far too often the perpetrators go free. In most cases charges are never filed, and in the rare event that they are, the police more often than not are acquitted due to “qualified immunity,” because it can’t be proven that the officers weren’t in fear for their lives when they pulled the trigger. Whether there was just cause for fear is never examined.

Incident depicts one such tragic case. In 2018, a probationary police officer (PPO) in the Chicago PD named Dillan Halley unloaded his clip into the back of Harith “Snoop” Augustus, a local barber. The entire altercation, and its aftermath, were recorded on closed circuit surveillance cameras and on the police bodycams. The film is a damning exercise in forensics, using expert editing to not only show what went down, but how those responsible went right to work creating a narrative to justify the shooting, encouraged by their superiors. Rookie cops are told right from the off how to deflect responsibility for their own deadly actions.

We watch as Augustus is stopped by an experienced black officer, who chats calmly with him. It appears he’s got a gun holstered on his body, but Illinois is a concealed carry state, so as long as he has a permit, he is well within his rights. As he tries to pull out his ID to demonstrate this fact, three white cops, all PPOs, surround him and attempt to arrest him. Scared, Augustus breaks free and runs into the street, where Halley promptly fires five shots, killing him fairly instantly. By the time ambulances arrive, he’s already dead. We see as Halley immediately starts trying to put the most positive spin on this, screaming that Augustus pointed a gun at him, and asking why he “made him” shoot, a common rhetorical device to put the blame on the victim. We then see Halley remove Snoop’s gun, still in the holster, giving immediate lie to his assertion and demonstrating irrefutably that he removed evidence from a crime scene.

In a sane world, that would cost Halley his job and his freedom. Instead, it’s just the beginning of the game to remove all liability. He and his partner, Megan Fleming, are quickly whisked away from the scene by a superior who calls in the shooting to the precinct, parroting Halley and Fleming’s version of the story, and assures them that they’ve done nothing wrong. Once safely away from the quickly gathering crowd of neighbors and witnesses, they finalize their story, and the superior officer tells them unequivocally to turn off their bodycams and not say anything incriminating while they’re on.

This shit is devastating, because it feels so thoroughly orchestrated. The entire “incident” took place over about 20 minutes, and the film is edited to keep as much of the action as possible in synced real time, splitting the screen into multiple segments to accommodate everything. A man is dead, the public is outraged, and the priority for the police is to protect their own and find some way, any way, to make it the dead man’s fault.

It’s yet another example of the disparities and systemic racial abuse that still goes on in this country, but thankfully, all of this footage is publicly available, so if the justice system isn’t willing to prosecute the case in a court of law, then it is left to filmmakers like Morrison and Kalven to do it in the court of public opinion. The backdrop of the film notes heavy tension in the air, as the city was days away from the trial of a different officer, one who killed 17-year-old Laquan McDonald and lied about the threat to his safety. A reckoning on racial justice and police brutality was supposed to result from it. Unfortunately, as Incident shows, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Instruments of a Beating Heart – Ema Ryan Yamazaki and Eric Nyari

The only nominee that doesn’t take place in the United States, Instruments of a Beating Heart is also the most uplifting of the set. Unfolding in a Japanese elementary school, the film is a sweet but crucial lesson for kids when it comes to taking risks, pushing past your limits, and working hard to succeed. It also shows the value of empathy and mentorship when things don’t work out.

Nearing the end of the school year, we meet Ayame, a cheerful first grader whose joy and enthusiasm shines through even though she and her classmates wear facemasks throughout and their desks are separated by plastic screens, indicating that this was filmed during or shortly after the COVID pandemic. As part of the welcoming ceremony for the incoming first years, Ayame and the other classes are going to perform an instrumental of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” Ayame is super excited to play an instrument, first auditioning to bang a large drum, and after coming up short, tries again with cymbals, and gets the part.

Over the next two weeks, the children rehearse constantly, but Ayame lags behind the rest, quickly losing her confidence. It doesn’t help when the teacher singles her out for being the only one not up to snuff. “Did you think it was over with the audition?” he asks, reducing the young girl to tears. Eventually, though, with the encouragement of her kind and supportive homeroom teacher as well as her friends, she catches up and has a great time.

This is such a simple story, but it has so many valuable lessons in it. We start off by seeing Ayame fail to land her preferred assignment, which makes her sad, but everyone is encouraged to keep trying. That’s a crucial thing for a child to learn. You won’t always win, but that doesn’t mean you should give up. More importantly, after Ayame succeeds in getting the cymbal spot, another girl in the class is also sad for missing out, so Ayame learns to not boast and to consider the feelings of others. It’s not all about her. Empathy, it’s a wonderful thing (the other girl aces the audition for triangles next to reinforce the first idea). When Ayame starts to fall behind, the instructor is strict, and he admits to it, because he knows that she can do it. He wouldn’t have let her pass the tryout if he didn’t. Have the courage to accept criticism and work to fix your mistakes. The rest of the world won’t go so easy on you. And when Ayame really feels like she’s letting everyone down, the homeroom teacher assures her that if it ever feels like it’s too much, she’ll be there to defend Ayame, so that she never stands alone. It’s an acknowledgement that well-meaning methods can still go too far, and when that happens, you need to be able to count on others to help.

Think about that. Some of the most essential behaviors that anyone can learn are perfectly distilled to a six-year-old in just a few short scenes. This is what happens when you give children the intellectual credit they deserve. Life is rarely fair, but you can do your part to make it fairer and better for yourself and others. It’s freaking beautiful. Also, in reference to the point I made in the preamble, kudos to Yamazaki for recognizing the need for efficiency, as this film is a cutdown of a feature she made in 2023 called The Making of a Japanese. I’m sure that full-length film has other insights, but she was able to get the key bullet points down to a tight 23 minutes.

The Only Girl in the Orchestra – Molly O’Brien and Lisa Remington

I mentioned on Monday that this is the only category where I didn’t see any of the nominees in advance, but I certainly could have here, as The Only Girl in the Orchestra was part of Netflix’s FYC campaign. It’s a sweet, straightforward look at the life and career of something of an unsung hero, and while I don’t think it rises to the level of the other four nominees, it certainly is pleasant.

The story is that of Orin O’Brien (director Molly is her niece, and sadly not the 24th Century offspring of Miles and Keiko), who in 1966 became the first woman to join the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, under the direction of Leonard Bernstein. Orin plays the extremely heavy and difficult double bass, and the film is a celebration of her impact on the music world as she enters her retirement at age 87.

We get a lot of interesting stories about life in the 60s, how her parents’ fame (she’s the daughter of silent and early talkie film stars George O’Brien and Marguerite Churchill) shaped her outlook on the entertainment industry as a career, and the truly weird (and borderline thirsty) press coverage she got as the first woman in the orchestra. Spending over 50 years performing and teaching, the time has come to hang it up and enjoy a life she’s earned for herself, illustrated through her move from the Manhattan apartment she lived in for most of that time to a more quiet house in the suburbs.

The core lesson from Orin is that it’s okay to be a roleplayer. Having seen how quickly her parents became disposable as they hit middle age, she knew that the limelight was not the place for her. She didn’t envy the pressure, and she most certainly didn’t want to follow in her parents’ footsteps and see work just dry up regardless of talent. So she opted for something steadier. She chose an instrument that not many played, became an expert at it, and found a position that allowed her tremendous artistic freedom while also providing a modicum of financial security. As she puts it, “Not everyone can be a general. You need soldiers.” One of the more fun anecdotes involves a time where she got lost in her music, not realizing that she was playing so aggressively that she overpowered the other sections, forgetting that the bass is a support instrument, not a lead. It was embarrassing in the moment, she said, but it was a truth she needed to learn.

In a weird way, though, this kind of makes the entire film unnecessary. Orin states quite early on that Molly had to convince her to even do it, because she didn’t want the attention. She likes that she has some fans, and that Molly sees her as an inspiration, but that was never her intent. All she wanted to do was good work, whether anybody noticed or not. She wasn’t there to break a glass ceiling, just to rosin a bow and help out the 80 or so other musicians around her. It’s a nice sentiment, and reminded me of my mom, who always said we did “too much” whenever we bought her more than one Christmas present each year. It speaks to her workmanship and humility. When I say the film is unnecessary, what I mean is that we’re not given a reason to care about her. I care because I love orchestral music and learning about how it all works, because I’ll never be able to play it. It’s also clear why Molly cares about her, because Orin’s her awesome aunt, and she wanted to do this tribute. But there’s no clear through line for why and how a general audience is supposed to be effective. Even the title is kind of misleading, because Orin was the first woman in the orchestra, not the only one that’s ever been. It creates a sexism angle that doesn’t really track with what we see (especially since Bernstein himself probably wouldn’t have even been interested, given his proclivities). It’s lovely, but inessential.

***

In a strange way, this entire field is kind of cyclical. We go from the lighthearted highlights of childhood in school, to the harsh realities teenagers are forced to learn because our government won’t do anything to stop wanton violence, to the state committing said violence, to a question of the ethics of doing so, to an old teacher passing on her knowledge to the next generation. Whether or not the pattern repeats depends on all of us.

As far as my preferences go, I look to two factors that stood out to me. For my top pick, I’m going with the film that best exemplifies all the themes presented from the nominees, as I think that’s the most impactful way to sum up the field. On a more meta and less heavy level, this same film also happens to have the most independent feel to it. If there’s one thing I’d say is a positive about streaming services, it’s that they’ve opened up more opportunities to view short films and documentaries, but this year’s set lays it on a bit thick, and there’s an odd corporate mechanism to four of the five nominees. We’ve got a Netflix documentary, an MTV/Paramount+ one, a New York Times entry, and one from The New Yorker. Only one seems to have been produced and distributed outside of that model, so for telling a story most true to its subject without any noticeable business influence, it gets my vote.

My Rankings:

1) Death by Numbers

2) Instruments of a Beating Heart

3) Incident

4) I Am Ready, Warden

5) The Only Girl in the Orchestra

Who do you think should win? Vote now in the poll below!

Up next, it was so much fun doing an Acting category yesterday, so LET’S DO IT AGAIN! Also, we’re just running out of categories at this stage, so like, we gotta. Wait, this feels oddly familiar, somehow. Oh well. It’s Best Actress!

Join the conversation in the comments below! Have you been able to catch a Shorts screening? Which of these stories sounds most intriguing to you? Have you ever even tried to lift a double bass, much less play one? Let me know! And remember, you can follow me on Twitter (fuck “X”) as well as Bluesky, and subscribe to my YouTube channel for even more content, and check out the entire BTRP Media Network at btrpmedia.com!

2 thoughts on “Oscar Blitz 2025 – Documentary Short”