Late in January, I had to take my computer in for service. It was the second trip to the Geek Squad in as many months. The problem was that my C drive was constantly filling up, causing my web browser to crash if I had more than one tab open, and frequently closing regular program windows while I had work in progress – work that I could not save.

I had a theory that some malware had gotten into my system, as the “free up space” warnings I got often referred to Chrome extensions that were just a random assortment of letters. Clearly these are not applications that I downloaded or installed willingly, and that was what was clogging up my digital gears. Upon the first visit, I learned that I was partially right. There were definitely some unwanted junk files and cookie bots, but the bigger problem was simply age.

I bought this machine back in March of 2019, nearly seven years ago, which in modern computing terms is an eternity. It was an upgrade over my previous laptop, and I made the investment thinking that it would help me with work, and that the expense would surely be alleviated through future gigs. Little did I know that I was in the midst of a nine-month period of unemployment, and a 13-month gap in work in my professional field. Sound familiar? I did eventually pay it off, but now that I’m in yet another lengthy hiatus – one that may become permanent – replacing it is simply not an option.

I knew from the moment I bought it that memory and storage would eventually become an issue. The computer has two hard drives. The C drive is meant to run apps, while the D drive is meant to store data and files. The latter had over a terabyte of space, but the former only had 128 gigabytes. By contrast, my first desktop in 2002 had 32 GB. Two decades-plus later, it’s simply not enough, as file sizes grow exponentially each year.

So the immediate concern was resolved, but the recommendation was that I “add storage” to the machine. They told me they could show me options and pricing right then and there, but I needed my computer back ASAP so that I could maintain the blog and do a couple side projects. I had already been without it for over a day, and I couldn’t afford any longer. Thus, I sat on the problem for several weeks, until after the holidays, to see how it developed. Even with the malware purged, I only got a few days’ worth of peace before the C drive filled again. I went back and got the ugly details. Yes, they could add storage, but not to the existing drive. They had to install a new one, which meant removing the old one. Some of the data could be transferred, but no program files other than those native to the system. It would cost me $200 for their smallest drive – another terabyte – but still far cheaper than the two grand or more that would be needed to get a new computer that met my personal and professional needs. When I got it back, I had to reinstall a few apps, but for the most part, the transition has been fairly painless.

Why am I telling you all this? Well, because two of the programs I decided not to reinstall were iTunes and Spotify. The former I would use to occasionally buy music, mostly during the 2010s as part of an annual mix CD I would give out to friends at Christmas, featuring what I thought were the best songs of the given calendar cycle. I haven’t used it in over a year, and one of the most annoying first world problems in existence is iTunes intruding on whatever I’m doing every Monday to get me to download and install the latest update, which was usually one new line of code.

The latter, I literally only used for the purpose of listening to the nominated soundtracks in the Original Score category. The streamer was clearly only concerned with getting me to spend money, with the interface filled with banner ads, playbacks paused to give me pop-ups asking me to pay for a premium subscription, and bringing the whole affair to a halt every third track to force me to sit through a full 90 seconds (minimum) of video ads that could not be skipped, and which were infinitely louder than the actual music I was listening to. I’ve never bought music through Spotify, and I was never going to pay for ad-free streaming, because I simply don’t care about modern music enough to justify the expense, which starts at $13 per month. It doesn’t sound like much, basically the price of a CD around the year 2000. The problem is, I haven’t listened to an entire CD’s worth of new music in a single month this decade. It would be wasted money.

More importantly, I had a much more tolerable alternative in the form of YouTube. The reason I went to Spotify is because, for a while, it was hard to get the entire soundtrack album on YT, and when I did, I would get unskippable ads after every track. But things have gotten better over the last few years. I have a Premium-Lite account on YouTube, which gives me ad-free viewing of everything but music, but since I don’t often look up music, that’s perfectly fine. I pay five fewer dollars per month than what Spotify wants, and while there are commercials in this one area, they’re far more manageable. They only come in after every five cumulative minutes of watching/listening, however many tracks that requires, the vast majority you can skip, and when you can’t, the interruption lasts no longer than 30 total seconds.

Have I bored you to tears yet? Well, sorry, but I needed something to talk about, because this year’s best soundtrack is so far ahead of the rest of the competition that it feels like the Music Branch genuinely struggled to fill the contest out to five nominees. I honestly expected them to nominate Diane Warren: Relentless (they did shortlist it) just to give her another bullshit nod that she had no chance of winning so they could create the illusion of a full contest.

This year’s nominees for Original Score are…

Bugonia – Jerskin Fendrix

Jerskin Fendrix’s music is, on the whole, a fun mix of traditional melodies, electronic distortions, and avant-garde subversions of tempo. He’s delightfully weird, which is why he fits in well with Yorgos Lanthimos, evidenced by his previous nomination for the score to Poor Things. Even the soundtrack to Kinds of Kindness had its charms… when it was something other than techno tracks for Emma Stone to dance to like she was a malfunctioning android.

These are good things to keep in mind, because the score to Bugonia is just awful. Like the film itself, there is promise, and a ton of buildup, but in the end it’s just a disappointment. Given that most of the film takes place in a basement with two people talking to each other in relatively hushed tones, it’s maddening that the bulk of the score involves high-pitched – and oppressively loud – strings and brass, which I remember caused me to constantly raise and lower the volume on my TV as I watched the movie, before I just gave up and resigned myself to struggling to understand some of the dialogue that was drowned out by the music.

It wouldn’t be so bad if there was a payoff for all the pain. A lot of the compositions feel like a pale imitation of the shower scene violin stings from Psycho, with the notable difference being that after the fifth repetition you actually start wishing you’d get stabbed several times to put you out of your misery. There’s no calm before the storm, just a 0-60 instant escalation, and an even faster and more sudden return to silence. There are at least recognizable notes and tones that resemble actual music, allowing the listener to remind themselves that this could have been a great companion piece to the larger film. But like the actual story, it feels half-baked, and there are times when it comes off as genuinely ill-advised.

Frankenstein – Alexandre Desplat

Of all the also-rans this year, Alexandre Desplat’s score for Frankenstein is the most intriguing and varied. Usually, you can count on Desplat for enjoyable, whimsical soundtracks that have their own identity. It’s a pattern that helped him break through in the mid-00s, becoming one of the most beloved film composers in the world, and which earned him two Oscars to date. He’s become a favorite of A-list filmmakers like Wes Anderson, and this is his third collaboration with Guillermo del Toro.

His signature style isn’t as apparent this time around, instead replaced with a more programmatic profile, similar to Peter and the Wolf. Each major character has their own theme that repeats as they wend their way through the story. Victor’s is fast-paced and energetic, Elizabeth has light, gentle strings, and the Creature has a mix of deep, oppressive woodwinds with tender piano melodies. As the plot goes on, variations are introduced, in keeping with the development and nuances of the core cast.

It’s an intriguing composition, and as I listened, I was able to close my eyes multiple times and imagine the accompanying scene to the cues. This could have been a legit challenger, but the distinctive tracks only make up about half of the score. Everything else is fairly standard orchestral fare. The tone and tempo rise and fall in line with the narrative progression, but at times it does feel run-of-the-mill. Mind you, even “regular” Desplat is still better than the vast majority of film scoring, and even in the lesser moments, you can detect the level of expertise in the arrangement. It’s a valiant effort, and in some years it could easily win, just not this year.

Hamnet – Max Richter

Max Richter’s soundtrack is largely light and ethereal, with a heavy emphasis on calming strings and melodic progression. You can detect the emotional journey of Agnes (and to a lesser extent Will and the children) as it goes on, creating a resonant, almost dream-like motif throughout. The problem is that this is basically all there is, and the same theme over and over again can’t really sustain itself as more than background music that you can ignore. This does thankfully change in the finale, but I’d argue that’s almost emotional manipulation at that point, because Richter makes sure that the score doesn’t intrude on the proceedings for 90% of the runtime, and then has it barge in without warning.

The most noteworthy thing that makes it stand out is sadly, one that you can only discover if you listen to the soundtrack in isolation and read the liner notes. Nearly half of the cues have titles beginning with the word, “Of.” There’s “Of Agnes,” “Of the heart,” “Of a ghost,” and several more. This is a cool bit of literary integration, giving us the impression that there’s a poetic angle to consider. It’s an interesting touch, but doesn’t do much to enhance the audio or visual experience. It’s just a fun aside. I’d argue that Bryce Dessner’s score for Train Dreams accomplishes the same goal without any extra tricks or accoutrements, but unfortunately, that candidacy stopped at the shortlist phase.

Essentially, this score is pleasant and competent, and would make for a mostly benign companion if you want to turn it on while reading Shakespeare’s works. As an Oscar candidate, however, it’s pretty much just… there.

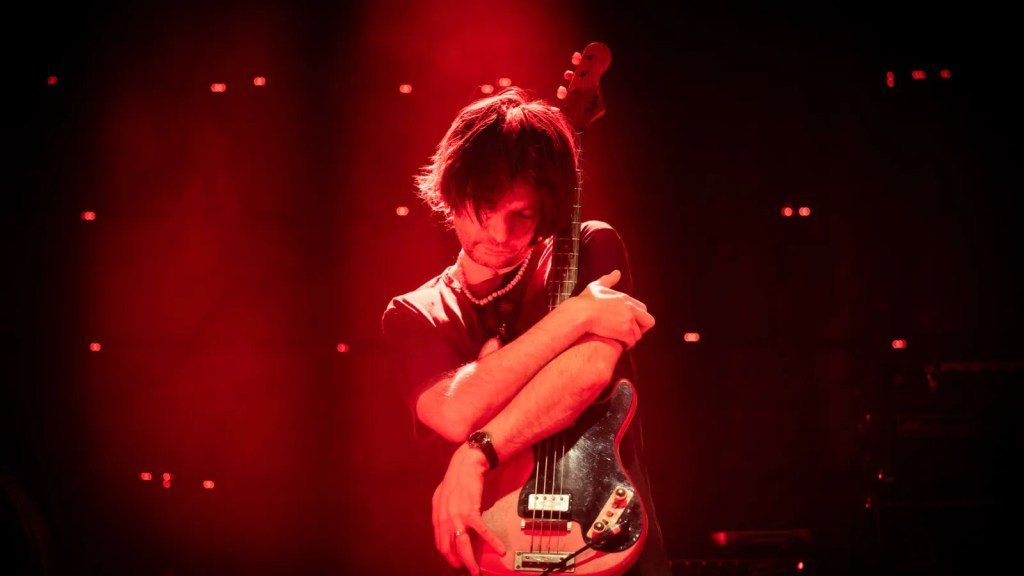

One Battle After Another – Jonny Greenwood

Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood is on his third Oscar nomination in the last decade, after Phantom Thread and The Power of the Dog, and his score for One Battle After Another fits into that set quite nicely (he also has BAFTA nominations for all three, as well as There Will Be Blood). He knows how to compose for stories about damaged characters, which isn’t all that surprising given his alternative rock bona fides, and since this is his fifth collaboration with Paul Thomas Anderson, he definitely understands his assignment each time out.

We get some welcome bits of development via the music. Like Frankenstein, there are noticeable cues for individual roles here, and there are creative twists within them. For example, the track devoted to Teyana Taylor’s Perfidia is peppered with police sirens in the background that melt into the high-pitch violins, an audial reminder of the danger she constantly faces as a revolutionary. There’s also some teasing taps of piano keys to needle the audience in tense situations as Pat/Bob and Sergio are on the run. It’s solid stuff.

The reason it doesn’t rise to the heights it should is two-fold. One is that several of the cues are based around the themes, motifs, and chord progressions of 1972’s “Dirty Work” by Steely Dan, which also features in the picture as a catalog track (stretching the definition of what an “Original” Score entails). This feeds into the second problem, the fact that the music that plays the biggest role in the film comes from the licensed tracks, such as Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger,” Ella Fitzgerald’s rendition of “Hark! the Herald Angels Sing,” and most importantly, Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” the referential lyrics of which form the call-and-response between Pat and Willa. These are the moments that are inextricably linked to the story, not Greenwood’s orchestral score. It’s perfectly fine, but not what we think of when we think of the music in this film, and as such, it shouldn’t win.

Sinners – Ludwig Göransson

Okay, we’re done with the participation trophies, now to the truly superlative. Göransson is already two-for-two in this category (Black Panther and Oppenheimer), and he’s about to go three-for-three. The Sinners score is leaps and bounds ahead of the other nominees, both a companion piece to the sublime narrative and a standalone work of art that tells its own amazing story through music alone. Göransson is proving himself to be a musical savant, and this is his greatest opus yet.

The score starts out slow, but still intense, with a mix of blues influences and guitar lines straight out of a Spaghetti Western. It helps set the stage for what’s to come, as the Jim Crow South represents an existential threat to Black music, and this subtle blend perfectly illustrates the fear and ambition that characters like Smoke and Stack have as businessmen/hustlers, as well as Sammie as a burgeoning musician in his own right (pointedly, Göransson records using the same Dobro guitar that Sammie has in the film). The infusion of a backing choir reflects the spirituality of the music and community of the era.

When Remmick shows up, things start to take a turn. Heavier themes begin to intrude on the overall motif, with individual lines and cues incorporating blues into a more country, then rock and roll style, highlighting the evolution of pop music in America while also nodding to the assimilation/appropriation of our collective history, and Remmick’s literal vampirism. As the party unfolds in the juke, Sammie’s rousing “I Lied to You” (itself nominated for Original Song), fades into a medley of African musical influences from the tribal past, to the soulful present, to the funk and hip-hop of the future to come, surrendering the euphoric melody into an experimental through line of all that was, and all that is to come.

Finally, as the tables start to turn, and more and more of the juke’s patrons are subsumed into the mass, the rock rhythms become overpowering, dominating the last third of the soundtrack, echoing Remmick’s power and threatening to swallow every ounce of the blues identity that Sammie was trying to forge for himself. Göransson leans into the stereotypes and tropes of so-called “devil music,” summoning an army of musical demons (both instrumental and choral) to lay waste to everything we thought we knew about where the melodies and harmonies were going. But then the Sun rises, Remmick and his horde are destroyed, and Sammie is left with a broken guitar, the music still alive in his heart, but badly injured. This is where we get the smooth yet tepid acknowledgement of the damage done, with a blues line that has endured everything that the people on screen have.

There are times when the soundtrack to a film can act as its own character. Sometimes that’s a good thing, sometimes it’s distracting, and more often than not, it’s done in the form of on-the-nose needle drops and catalog entries. Here, Göransson’s score acts as the omniscient musical guide to all that transpires in Sinners, a recognition that music as a communal art form has to be preserved in order for culture to survive. And so, Göransson puts it through its paces, forcing it to go along with the cast – and the audience – on the journey to that realization and actualization. This isn’t just a distinct, identifiable presence that feels like another member of the ensemble, but rather a symbiote, willingly and instinctively giving itself to everything around it in a somewhat ironic juxtaposition to what Remmick tries to take by force, and it’s motherfucking glorious.

***

So yeah, um, that’s pretty much it, I guess. This category has been a lock since the moment the movie was released back in April. Even when I left the theatre after watching it, every conversation I overheard on the way out included some mention of the soundtrack needing to get an Oscar. Of the record-breaking 16 nominations the film has, this is the one I think we all agree it’s guaranteed to win. I always prefer it when there’s a robust competition, but sometimes you just know what the right answer is, and it almost feels like a disservice to even pretend anyone else could take it.

My Rankings:

1) Sinners

2) Frankenstein

3) Hamnet

4) One Battle After Another

5) Bugonia

Who do you think should win? Vote now in the poll below!

Up next, we wrap up Week 2 with another video breakdown, this time for the category I’m likely the least qualified to judge. Pray for my sanity as I pull stuff out of my ass in hopes of sounding like I know even remotely what I’m talking about. It’s Costume Design!

Join the conversation in the comments below! Which nominee comes closest to offering a challenge to Göransson? Should we have just canceled the competition and awarded him the Oscar by fiat? Do you ever play film scores in the background as a study aid? Let me know! And remember, you can follow me on Twitter (fuck “X”) as well as Bluesky, subscribe to my YouTube channel for even more content, and check out the entire BTRP Media Network at btrpmedia.com!

One thought on “Oscar Blitz 2026 – Original Score”